This summer, the UK enacted the long-anticipated Data (Use and Access) Act 2025 (“DUAA”), the first major amendments to the UK’s data protection legislation since Brexit. The changes include substantial reforms to the rules on automated decision-making (“ADM”) involving personal data. While the government has not yet confirmed an implementation date, the new regime is expected to take effect in 2026, subject to secondary legislation and further guidance from the ICO.

In this post, we examine DUAA’s impact on ADM and how these changes compare with the position under the EU GDPR. Although DUAA moves the UK away from the EU’s general prohibition on ADM, the most effective compliance approach in both jurisdictions likely remains to involve human oversight over any automated decisions to prevent them from triggering the respective ADM requirements.

The Current EU Framework

Subject to limited exceptions, the EU GDPR prohibits businesses from making decisions based “solely” on automated processing of personal data– including profiling – where the decision produces legal or similarly significant effects for the underlying individual (see Art. 22(1)).

Decisions based “solely” on ADM: Under the EDPB Guidelines, a decision is “solely” automated where it is made without any meaningful human involvement in the decision-making process. The ECJ’s Schufa decision, and the Austrian court’s decision regarding the Public Employment Service indicate that meaningful human intervention requires active, informed, and independent judgement – not merely a rubber-stamping of an automated result:

- The mere presence of a human at the end of the process does not necessarily mean there is no ADM, particularly where the human’s role is purely formal or where automated outputs are almost always followed without question.

- Ensuring that human reviewers receive clear guidance and training on the range of factors to consider – beyond the automated output – strengthens the argument that the final decision involves genuine human judgement.

- Establishing monitoring mechanisms to identify reviewers who routinely adopt the automated score, and conducting spot checks of their assessments, can further support the position that the process is not “solely” automated.

- Requiring a human decision-maker to engage directly with the individual concerned (for example, through an interview or discussion before the decision is finalised) provides strong evidence of meaningful human involvement.

That “produce legal or similarly significant effects”: Per GDPR Recital 71, this covers decisions such as the automatic refusal of a credit application made online, or the use of fully automated e-recruitment tools without human review. Other examples include (i) an e-commerce platform that automatically refuses to sell certain products to a customer based on their purchase history or location; (ii) a ride-hailing app algorithm that automatically deactivates a driver’s account due to low ratings; or (iii) an insurance algorithm that sets or denies coverage and premiums without human review.

Limited exceptions: ADM is permitted only in narrow circumstances (see below) – and, even in these cases, the controller must implement appropriate safeguards. An even more limited set of exceptions apply to ADM involving special category personal data.

In practice, these exceptions are interpreted narrowly and, on a plain reading, few ADM activities can be carried out in full compliance with the GDPR, leaving most organisations cautious about relying on automated processes for significant decisions.

The UK’s Pivot

Although DUAA effectively retains the EU’s definition of ADM, ADM involving non-special category data will now be prima facie permitted (rather than prima facie prohibited) if certain safeguards are implemented. In contrast, ADM involving special category data continues to be prohibited except in very limited circumstances.

The practical impact of this change will, therefore, depend on the type of decision being made, and the nature of the data used. For example:

- Recruitment Pre-Screening: The use of an AI system for candidate pre-screening without subsequent human review is generally prohibited in the EU subject to applicable exceptions, but it would be generally permitted in the UK, provided safeguards are in place.

- Credit Decisions Using Health Data: Using health data to make automated credit-scoring decisions are prohibited under both frameworks unless the individual explicitly consents to it, or one of the statutory exemptions applies, and appropriate safeguards are in place.

This reform could materially affect how organisations deploy AI in decision-making. Although not every AI-driven outcome constitutes ADM, in practice there is often considerable overlap – particularly where AI tools operate with minimal or no human input. By relaxing the general prohibition on ADM involving non-special category data, DUAA creates greater legal certainty for businesses seeking to integrate AI into operational or customer-facing processes.

Head-to-Head Summary

| EU GDPR | UK GDPR as amended by DUAA | |

| ADM Definition | Both regimes define ADM as decisions based solely on automated processing (i.e., with no meaningful human involvement) – including decisions reached by means of profiling – that have legal or similarly significant effects for the underlying data subject. | |

| Default Rule | ADM involving non-special category data: is generally prohibited, subject to three limited exceptions (see below). | ADM involving non-special category data: is generally permitted, provided relevant safeguards are in place. |

| ADM involving special category personal data: is generally prohibited, subject to two limited exceptions (see below). | ADM involving special category personal data: is generally prohibited, subject to limited exceptions (see below). | |

| Exceptions | ADM involving non-special category data: permitted only where:

(a) It is necessary for entering into, or for the performance of, a contract between the data subject and the controller; (b) It is authorised by Union or Member State law which also lays down suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights and freedoms and legitimate interests; or (c) It is based on the data subject’s explicit consent. |

ADM involving non-special category data: N/A – this is generally permitted. |

|

ADM involving special category personal data: permitted only where: (a) It is based on the data subject’s explicit consent; or (b) It is necessary for reasons of substantial public interest. |

ADM involving special category personal data: permitted only where:

(a) It is based on the data subject’s explicit consent. (b) It is necessary for entering into, or for the performance of, a contract between the data subject and the controller, and processing is necessary for the reasons of substantial public interest. (c) It is required or authorized by law, and the processing is necessary for the reasons of substantial public interest. |

|

| Safeguards

|

Where businesses are relying on necessity and consent exemptions to undertake ADM, they must implement “suitable” safeguards to protect the underlying individuals’ rights, freedoms, and legitimate interests.

At a minimum, those safeguards must include the right for the underlying individual to: (a) obtain human intervention in the decision-making process; (b) express their point of view regarding the decision; and (c) contest the decision. When relying on the domestic law exception to undertake ADM, it is inferred that the business must lay down suitable measures to safeguard data subject’s rights as outlined under the relevant domestic law. When relying on the exceptions to use ADM based on special categories of personal data, there must be suitable measures to safeguard the data subject’s rights and freedoms and legitimate interests. |

Businesses must ensure that:

(a) the individual is provided with information about ADM-related decisions taken about them. (It is unclear whether this requirement simply reinforces the transparency requirements noted below, or if it is a new transparency obligation). (b) the individual has a way to: i. make representations about such decisions; ii. obtain human intervention in the decision-making process; and iii. contest the decision. [See Art.22C(2) UK GDPR] |

| Additional Transparency Requirements | Businesses must provide individuals with information on the existence of ADM, including profiling, and meaningful information about the logic involved, including its significance and potential consequences. [See Art. 13(2)(f) and 14(2)(g) EU GDPR] |

Same as under EU GDPR. |

Key Takeaways

- Meaningful human involvement remains the safest course. Even with the UK’s planned relaxation, the most reliable way to avoid falling within the ADM regime remains ensuring that a human meaningfully contributes to the decision-making process. Structuring use cases around this principle may offer a practical route to compliance.

- If ADM is necessary, the most practical solution may be to rely on consent (though its use remains limited). When ADM is unavoidable, explicit consent may offer a lawful route to compliance – though it is not always feasible to obtain freely given consent. For example, credit applicants are unlikely to be given a free choice to consent to ADM if this is a condition of apply for credit, and valid consent is typically challenging to obtain in an employment context due to the asymmetry of power between employer and employee. In these circumstances, ensuring there is meaningful human involvement, such that the decision does not constitute ADM, remains the safest course of action.

- Beware of profiling -related compliance challenges. While much of the regulatory focus falls on ADM, profiling remains a distinct and frequently misunderstood concept. Profiling covers automated processing used to evaluate personal aspects of an individual – such as analysing or predicting performance, preferences, behaviour, or location – and does not necessarily need to result in a fully automated decision to be regulated. The boundary between profiling and ADM is not always clear, particularly where profiling outputs strongly influence human decisions. These challenges will continue with the revised UK GDPR so that even where ADM is not used, businesses engaging in profiling will need to consider the associated risks carefully.

****

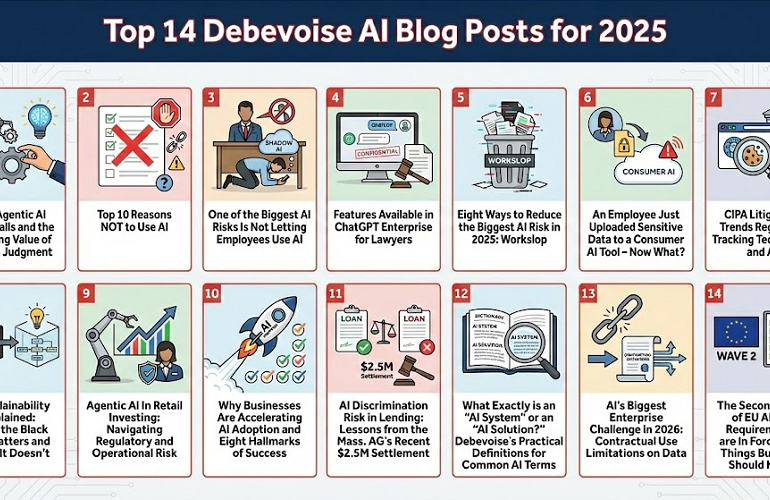

To subscribe to the Data Blog, please click here.

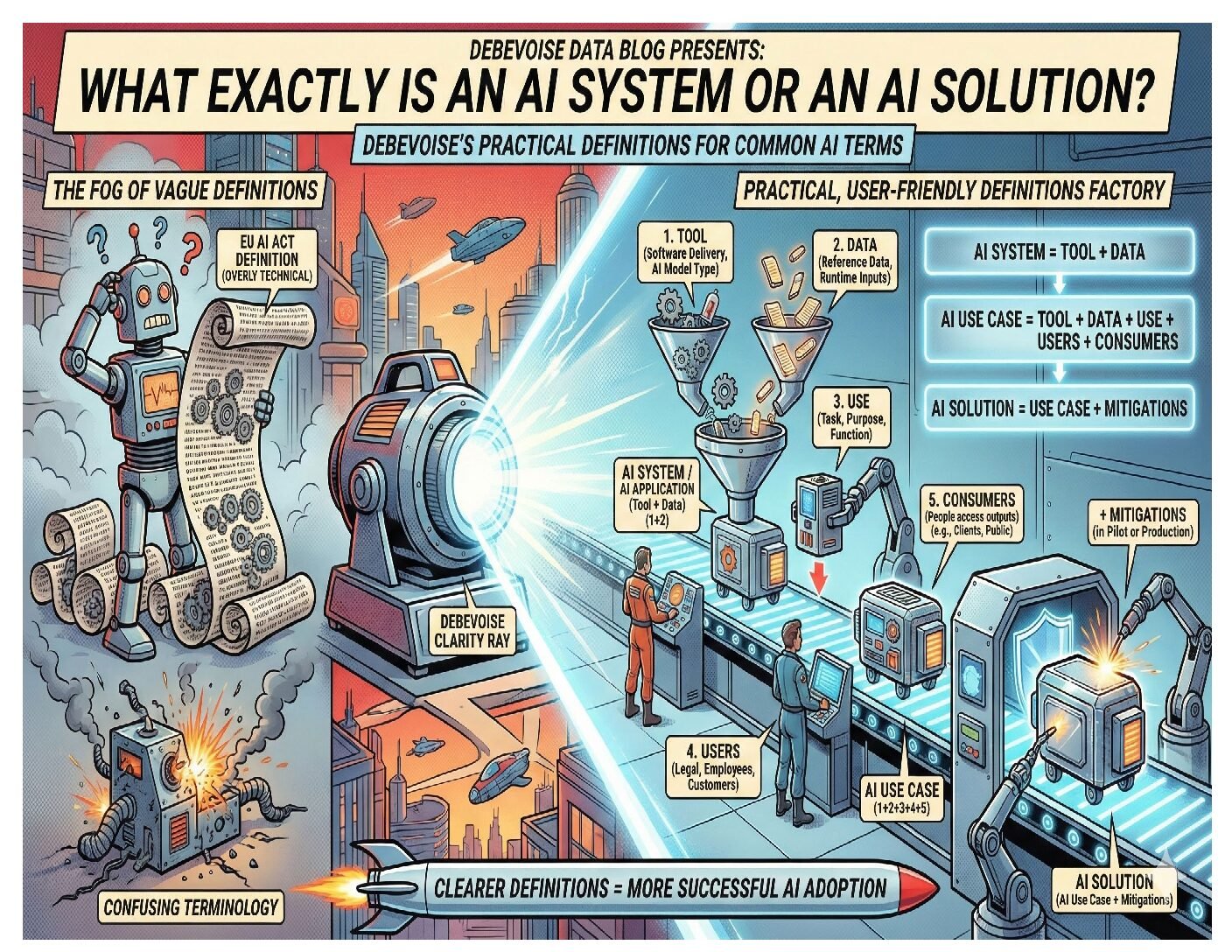

The Debevoise STAAR (Suite of Tools for Assessing AI Risk) is a monthly subscription service that provides Debevoise clients with an online suite of tools to help them fast-track their AI adoption. Please contact us at STAARinfo@debevoise.com for more information.

To learn why we added a CAPTCHA to the blog, click here.

The cover art for this blog was generated by ChatGPT-5.